In the month of December, a time when many Americans celebrate major religious holidays, TCIPS is directing its focus toward the intersections of psychedelics and various religions. As Judaism is such an important part of my identity, I was excited by the prospect of exploring the ways in which it converges with the realm of psychedelics.

Hanukkah, the Jewish Festival of Lights, begins on the evening of December 7 and lasts until the evening of December 15. It commemorates the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem during the second century BCE after the Maccabees successfully rebelled against Seleucid King Antiochus and his forces, who had invaded Judaea, persecuted the Jews, and desecrated the temple. After Judas Maccabeus entered the desecrated temple, he found just enough oil to burn for only one day—but miraculously, it burned for eight days. To celebrate this miracle, we celebrate Hanukkah for eight nights and light the menorah, adding an additional candle each night until all eight candles are lit. Although Hanukkah actually is not considered a major holiday in the Jewish religion, it was Americanized during the past century, transforming into the Jewish counterpart of Christmas.

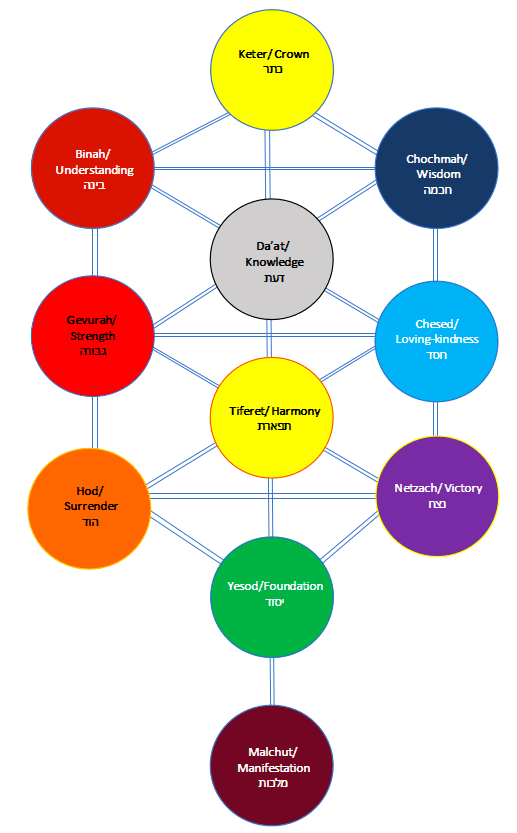

When I reflect on the potential intersection between psychedelics and the reflective aspects of many Jewish holidays, I cannot help but think about Kabbalah. Kabbalah, translating to “received,” is Jewish esoteric mysticism that delves beyond what is explicitly written in the Torah as a way to reach God directly. I first learned about Kabbalah at the age of 18 in Tzfat, Israel, a major center for Jewish mysticism. It was there that the Kabbalistic Tree of Life captured my attention—an intricate tapestry with ten sefirot, “emanations” of the higher immaterial realm known as Ain Soph Aur, or “the limitless light.”

The Tree of Life, as depicted above, visually organizes these sefirot into pillars, with negative (left) and positive (right) poles, and a delicate balance between the two—the leftmost pillar is Severity, representing passivity, form, and restriction; and the rightmost is Mercy, the positive pole, representing activity, movement, and energy. The sefirot are also laid out horizontally into triads—the Intellect Triad (Understanding, Knowledge, Wisdom), the Emotion Triad (Strength, Harmony, Loving-Kindness), and the Instinct Triad (Surrender, Foundation, Victory)—with a sefirah above (the Crown) and below (Manifestation). The top of the tree is the closest to Ain Soph Aur, whereas the bottom is the most material, closest to the physical world. While I was in Tzfat, I was in awe of the creative, colorful, and abstract artwork inspired by the Tree of Life and other Kabbalah concepts by artists like David Friedman. To this day, prints of his pieces A Tree of Life for Those Who Hold It (top) and The Holy Palace (bottom) hang on the wall in my bedroom.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life greatly reminds me of the mystical insights that are often reported during psychedelic experiences—perhaps it could serve as a framework for understanding altered states induced by psychedelics. Research suggests that psychedelics may enhance sefirot in the Tree’s Intellect Triad, potentially rewiring neural pathways. One paper reviewing the literature discussed how psychedelics are able to enhance people’s perception of meaning and are often described as magnifiers, amplifiers, and augmenters of consciousness. Another article looking at conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with the psychedelic drug psilocybin asserted that psychedelics can “disrupt stereotyped patterns of thought and behavior by disintegrating the patterns of activity upon which they rest...”

Psychedelic effects also align with the Tree’s Emotion Triad. One study demonstrated that MDMA, dubbed the “love drug,” can promote social bonding and love. Another study that administered psilocybin to participants who undertook meditation/spiritual practices found that the two high-dose groups (one with standard support for spiritual practices, and one with high support), as compared to the low-dose group, demonstrated “large significant positive effects on long-term interpersonal closeness, gratitude, life meaning/purpose, forgiveness, death transcendence, daily spiritual experiences, religious faith and coping, and community observer ratings.” These parallels between Kabbalah’s teachings and psychedelic effects evoke a profound synthesis of ancient wisdom and modern scientific inquiry.

Venturing into contemporary narratives, connections between psychedelics and Judaism continue to unfold, often emphasizing the power of psychedelics in religious and cultural exploration as well as the healing of intergenerational trauma. In an illuminating interview by Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB), Rabbi Jose Rose discussed the convergence of Kabbalah and psychedelics. He describes Kabbalah as an “important way for [contemporary Jews] to deepen their connection to their religious lives,” noting that “psychedelics are known to open up mystical experiences for people and allow people to see the world in new ways with a sort of elevated consciousness.” To Rose, many aspects of Judaism—including religious consciousness as well as the intergenerational trauma that Jews have endured as a persecuted minority—evoke a deep curiosity of the self and provide an openness to new ideas. Psychedelic-assisted therapy can allow for such self-exploration and inner healing.

Jewish leaders have not only underscored the therapeutic potential of psychedelics but have even formed underground psychedelic communities. In the 1960s, Hasidic Rabbis Schachter and Carlebach led LSD trips in synagogues, using Kabbalistic references and Jewish texts as the “primary lens through which they would understand their psychedelic experiences.” Recent endeavors, like the underground psychedelic group of Hasidic and Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn—dubbed “The Magic Jews”—highlight the enduring spirit of psychedelic exploration within the context of Judaism.

The founding of The Sacred Tribe, a Kabbalistic, Jewish Congregation founded by Denver Rabbi Ben Gorelick in 2018, is a contemporary testament to the intersection of psychedelics and Judaism. The synagogue, engaging in psilocybin-facilitated exploration during weekend-long retreats, offers its more than 270 members a transformative journey with guided breathing exercises, personal reflections, and communal discussions. Despite the positive potential of such retreats, legal complexities remain—although Denver decriminalized personal possession of psilocybin in 2019, buying, selling, and growing beyond a “personal” amount is still illegal. Such complications demonstrate the delicate balance between legal frameworks and religious exploration involving psychedelics.

As a “new(ish) movement based in old tradition” of psychedelic use for Jewish spiritual exploration has been arising for decades, the first-ever Jewish Psychedelic Summit occurred in May 2021, hosted by Madison Margolin, co-founder and Managing Editor of DoubleBlind; Natalie Ginsburg, Global Impact Officer at Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS); and Rabbi Zab Kamenetz, founder and CEO of the Jewish psychedelic support nonprofit Shefa. The summit provided a platform for Jewish luminaries, rabbis, therapists, mystics, and scholars to delve into the past, present, and future rituals and healing potential of psychedelic Judaism. According to Ginsberg, it was “one of the first vehicles to allow more of the [Jewish psychedelic] community to coalesce because for so long so many people were working in their individual spaces” and it intrigued people who felt disconnected from Judaism to explore this new avenue to reconnect with it.

As I light the menorah candles this Hanukkah, bridging Jewish traditions, history, and unity, I cannot help but think about the future of the religion and culture. Psychedelic Judaism seems like such a promising approach for self-exploration, religious introspection, healing Jewish trauma, and fostering a sense of community. I’m excited for this movement's continued growth, promising fresh perspectives within the ever-evolving tapestry of Jewish spirituality and community.

by Dana Lane

Fascinating!

Love this article! So much to explore!